In this post we explore the Cognitive Triangle, or Triangle of Experience – a tool used in cognitive behavioural therapy to understand how our response to the world creates our experience of it.

June has arrived, and last weekend my partner Andrew and I went for our first hike of the season. We’d both set goals to get into better shape, and the Spring weather was too good to pass up.

On Friday, we agreed that a hike would be a great idea. On Saturday, we decided where we’d go, and we agreed to leave at 9am on Sunday. On Sunday I got up early, intending to enjoy some quiet morning-time before heading out.

Then, the thoughts started:

- “I’m so out of shape.”

- “This is going to be hard.”

- “My legs look so fat in these shorts.”

- “How could I let myself gain this much weight, again?”

- “People are going to see me sweaty and struggling, and they’re going to judge me for letting myself get so fat.”

- “This is going to be awful.”

- “I can’t wait for this to be over.”

And what did these thoughts do to my peaceful Sunday morning? They absolutely obliterated it.

I spent the entire morning actively dreading the hike we were about to take, rather than enjoying the beautiful sunrise and using the time to relax and re-charge as I had intended. I was filled with dread and shame and resigned myself to the worst.

And the hike itself?

We went, and I hiked, but with internal reluctancy and impatience. I barely noticed the scenery, and I hardly spoke to Andrew. I was laser-focused on how much time was left until the end.

During the hike, I paid very close attention to how difficult it was, to how hot it was outside, to the discomfort in different parts of my body, and to the time on my phone that was an ever-present reminder of how much longer I had to endure this ordeal.

But the ordeal was of my own making. It came from a set of completely optional, unhelpful thoughts. The hike wasn’t actually that difficult, and my body wasn’t in an excessive amount of pain or discomfort, but the difficulty and discomfort that WERE there felt all-encompassing, and they were amplified by how much attention I was giving to them.

All of those Sunday-morning thoughts were there, begging for evidence; focusing on the pain in my body, the hot temperature, and a general lack of enjoyment all confirmed my predictions that this hike was going to be hard, that I was going to struggle, and that I was too out of shape to enjoy it.

This isn’t about manifestation or energy frequencies or karma; it’s about confirmation bias and the brain’s tendency to look for evidence to confirm what it believes. The brain doesn’t want to prove itself wrong.

Imagine if, instead, I spent Sunday morning thinking more useful thoughts:

- “The weather is so beautiful; I can’t wait to go outside and enjoy it.”

- “I’m so lucky to be here in Vancouver with this beautiful Spring weather!”

- “I have strong, powerful legs; hiking is no problem for me.”

- “Working out is supposed to feel like work; that’s how you know it’s working.”

- “This will make me stronger and healthier.”

- “Exercise is a celebration of what my body is capable of.”

- “It will be fun to get outside and explore somewhere new with Andrew.”

- “I’m looking forward to catching up with him out in nature, away from our phones and screens.”

- “I’m so excited to breathe in the fresh ocean air, and to take in the sights and sounds of the forest, and to get away from the city.”

- “With every hike I become a fitter, healthier, and stronger person.”

These thoughts would have generated a completely different experience before, during and after the hike, because my mood, and the sensations I was paying attention to, and the feelings I was generating within myself, would have been different.

These thoughts would have generated pride, determination, motivation and excitement. After a hike accompanied by thoughts like these, I would have felt accomplishment and satisfaction, not relief and shame.

Sure, the parts of my body that hurt would still have hurt, and the sun would have still felt hot, but my experience of it would have been much more enjoyable.

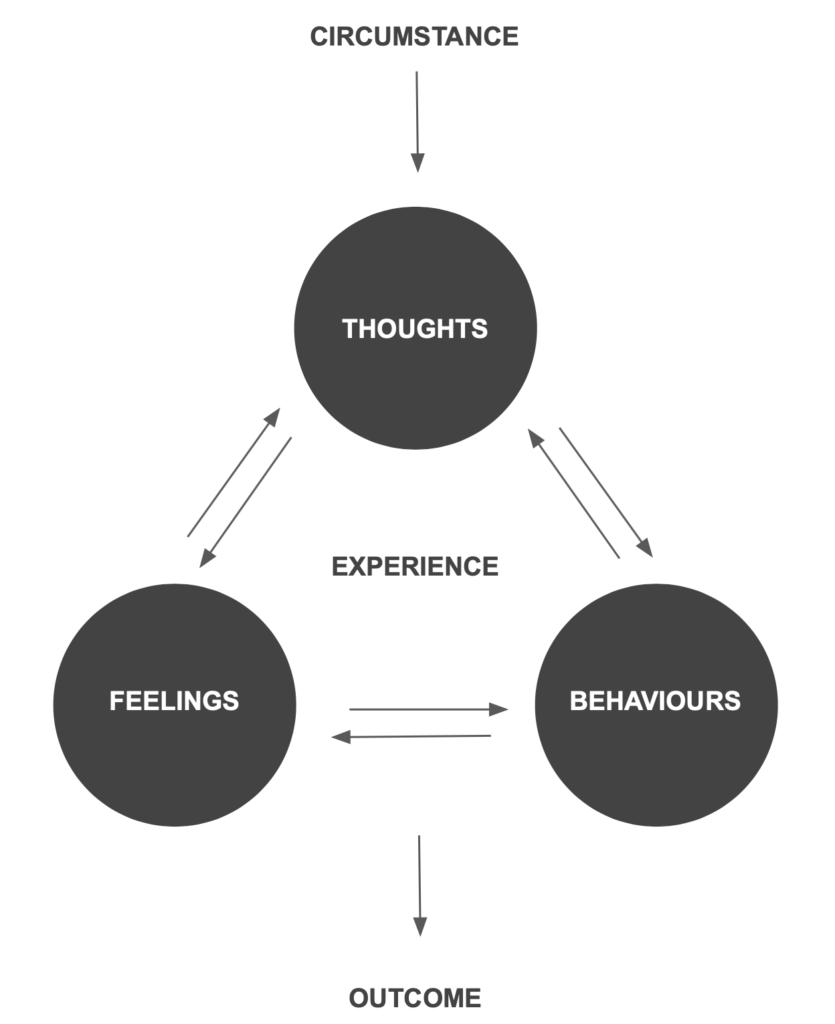

This phenomenon is well-established in the field of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, and it’s sometimes referred to as the Triangle of Experience or the Cognitive Triangle. The basic premise is that in any situation or circumstance, your thoughts, feelings and behaviours work together to create your experience of the situation or circumstance, which in turns creates your outcome.

It often cascades downwards in this order:

Circumstance > Thought > Feeling > Behaviour > Experience and Outcome

The beauty in this concept is that we can deliberately chose an experience that better serves us by intentionally choosing to think different, more useful thoughts.

Sounds good, but how do we choose different thoughts?

The first step is mindfulness: you must notice that you’re in a Cognitive Triangle that isn’t serving you (i.e. that you’re having a thought, feeling an emotion, or behaving in a way that you wish to change). Mindfulness takes practise, and meditation is a great way to strengthen your mindfulness-muscle. Another way is to practise pausing in the middle of your busy day, and checking in with your physical senses: what do you see, hear, feel, taste and smell?

Once you’re aware that you’re in a Triangle you’d like to change, you can decide on and practise different thoughts, based on the emotions and behaviours that those thoughts will generate for you. It’s a simple yet powerful truth that what you think is a choice, and that choice is always available to you.

Thoughts are simply sentences in your mind, and with mindfulness you can become aware enough to swap-in new ones in-the-moment. You can also practise and engrain new thoughts by writing them down (“scripting” them, if you will) and reading them frequently (ideally daily for several weeks). Read them slowly, allowing each word to sink in. Practise recalling them whenever you feel yourself being pulled into your original Triangle. With time and practise, the new thoughts, and subsequent feelings and behaviours, will become more automatic.

Here’s another example to help illustrate the idea.

Imagine you have a presentation coming up at work for a large group of your colleagues.

Thinking thoughts like “This has to be perfect,” “I don’t know what they’re going to think,” and “I can’t wait until this is all over and I can relax again” will generate feelings of anxiety and resistance. To ease those feelings you might avoid preparing, or you might spend too much time over-preparing. Either way, your efficiency is down and your stress is up.

Instead, in the days and hours leading up to the presentation, you could practise thinking “This is a great opportunity to share my idea,” “My co-workers are all rooting for me to succeed,” and “Any negative feedback I might get is an opportunity to improve [the idea, project, proposal, etc.].” These thoughts will generate feelings of motivation and resilience. You’ll be more likely to put in the work required to be well-prepared, without feeling the need to achieve perfection or to procrastinate. And odds are you will show up for the presentation with more confidence and be more engaged with your audience, increasing the chance that the talk will go well.

My hike last weekend was a much-needed reminder that powerful thinking is an intentional act; it doesn’t happen by default. We’re going camping next weekend, at a park with lots of beautiful mountain- and river-side hiking trails, and I already know which set of thoughts I’ll choose and practise thinking.

SOMETHING(S) TO PONDER

What’s a circumstance or situation where you’re struggling right now?

What’s an unhelpful thought about it, that your mind likes to play on repeat?

What experience (i.e. feeling and behaviour) is that thought creating for you?

What’s a more helpful or useful thought you could try instead?